Schools

Arizona State University: ASU Engineering Faculty Share Memories Of Late Professor Matt Witczak

See the latest announcement from Arizona State University.

Gary Werner

2022-02-14

Find out what's happening in Tempefor free with the latest updates from Patch.

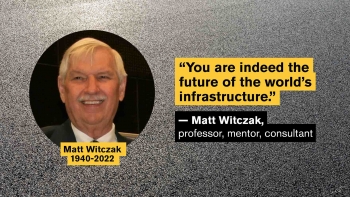

Matt Witczak believed the true measure of a professor is not the publications and citations accrued, but the support extended to peers and students.

By that human measure, Witczak was exemplary. Across 47 years at two universities, the Arizona State University professor emeritus devoted himself to the education of more than 5,000 civil engineering students, including service as graduate adviser to 70 of them.

Download Full Image

Find out what's happening in Tempefor free with the latest updates from Patch.

Consequently, the news of Witczak’s death on Jan. 18 sparked an outpouring of tribute from the many people who knew and deeply admired him.

“Matt was a renowned researcher and a highly sought-after industry consultant,” says Sandra Houston, an emeritus professor of civil and environmental engineering in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at ASU. Houston also was the person who recruited Witczak to ASU, and says she felt fortunate to have participated in bringing such high-caliber talent to the civil engineering program.

“His leadership drove, what is today, the most advanced and impactful research on pavement design and analysis. But he devoted so much of his time to mentoring younger faculty members and students. He was genuinely caring toward everyone around him,” she says. “We were all fortunate to have Matt’s presence in our lives, and we were very saddened to hear about his passing.”

Witczak was a professor of civil engineering at ASU from 1999 until his retirement 2011. He came to Arizona after more than a quarter century of teaching and research at the University of Maryland. Earlier in his career, Witczak was a special projects engineer for the Asphalt Institute, an international trade association. He also served as a combat engineer and intelligence officer in the U.S. Army.

“I had the utmost honor to have him as a mentor and work with him at both ASU and Maryland,” says Kamil Kaloush, a professor of civil and environmental engineering in the Fulton Schools. “He was an inspiration to me as well as many others through his mentorship, scholarship and research contributions in the field. He truly changed our lives and career paths for the better.”

Witczak co-authored the world’s foremost textbook on pavement design and analysis. He also helped lead the development of widely influential guidelines on airfield design and management. His expertise took him to more than 75 countries on behalf of the United Nations, the World Bank, the U.S. Armed Forces, as well as many institutes, associations and corporations.

“We were all inspired by his passion for life and work, as well as his strength and never-ending generosity. The memories of great moments we had together are the best way to celebrate his life and his legacy.”

— Claudia E. Zapata, Witczak's wife and associate professor of civil and environmental engineering in the Fulton Schools

Ram Pendyala, who works in the field of transportation and serves as the director of the School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment, one of the seven Fulton Schools at ASU, noted that Witczak earned the highest respect of both the research and industry communities.

“His passing is a huge loss to the transportation profession, and we will greatly miss his wit and wisdom,” Pendyala says.

Over the course of his career, Witczak received multiple distinguished awards from the Asphalt Institute, the Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists, the National Asphalt Pavement Association, the Transportation Research Board of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, as well other professional bodies and technical journals.

“Matt was truly a giant in the pavement design and research field,” says George Way, chairman of the board of the Rubberized Asphalt Foundation and a retired chief pavement design engineer for the Arizona Department of Transportation. “I am confident that the legacy of his accomplishments will continue forever.”

Witczak acknowledged that he had many opportunities to leave academia for lucrative commercial work. But “the interaction with bright young minds and the desire to better understand my technical discipline always led me back to being a professor,” he said.

While at ASU, Witczak founded the Advanced Pavements Laboratory to conduct comprehensive research that has become recognized for its national and international importance. He also led creation of the Arizona Pavements/Materials Conference as a means for academic and industry professionals to discuss advances in design, construction and technology.

Bob McGennis, a technical manager for asphalt at the HollyFrontier corporation, met Witczak in 1980 and stayed connected with him throughout his 40 years in the roadway construction industry.

“I remain in awe of Matt as a person, researcher and engineering educator,” McGennis says. “Like many others, the arc of my career was positively influenced by my association with him. It was my very good fortune to have known him.”

In 2017, the Arizona Pavements/Materials Conference organizing committee established the Dr. Matthew W. Witczak Endowment in his honor to provide scholarships, fellowships and other resources to enhance the academic experiences of those pursuing a career in pavement engineering. Pendyala believes the endowment will carry forward Witczak’s legacy through the education and training of the next generation of pavement professionals.

During his final lecture at ASU, Witczak reminded civil engineering students to stay connected with the academy in their roles after graduation because “higher education is not completed with a university degree. Rather, it begins with one … (and) we need to reduce the technological gap between the current state of the art and the current state of practice.”

He also extended his best wishes and highest hopes to each of them during their professional journeys, saying, “You are indeed the future of the world’s infrastructure.”

Can a person with no formal power create social change?

Students in Arizona State University's Master of Science in organizational leadership program recently learned that the answer is a resounding “yes."

Photo by Nick Fewings on Unsplash

Download Full Image

On Jan. 27, Gary Shepherd shared with students in Elizabeth Castillo's course, OGL 550: Leading Organizational Change, the story of how he created a peer education program while incarcerated in Florence, Arizona.

"His leadership launched a program that became a statewide model for inmates to develop skills, attitudes and behaviors needed for successful release and re-entry into society," said Castillo, assistant professor in the College of Integrative Sciences and Arts' faculty of leadership and integrative studies.

Shepherd began his story by sharing the missteps that led to his life sentence at age 20. In prison, he started looking for answers to what led him down that path.

He told students that he became an avid reader of philosophy, science, psychology and history to find the meaning of life (see his interdisciplinary reading list in the image below). His quest for knowledge and self-awareness led him to evolutionary science. Shepherd said he was awestruck by the recurring pattern of increasing complexity and higher levels of order that cooperation and prosocial behavior made possible. He was also impressed that understanding evolutionary principles enables better foresight.

Handwritten reading list by Gary Shepherd. Photo courtesy Gary Shepherd

"Having a deep understanding of evolution’s principles enables you to see the root of a problem before the seed has even been sown," Shepherd said.

One principle in particular surprised him — that science has shown cooperation enables the long-term success of groups. This flew in the face of everything he'd been taught about the importance of competition and having a "survival of the fittest" mentality, he said, but matched up well with his own experiences in prison, which validated the power of cooperative advantage. He saw firsthand how inmates’ social structures and norms helped to keep rogue troublemakers in check.

After gaining a basic understanding of evolutionary principles through reading, Shepherd connected with renowned evolutionary biologist David Sloan Wilson to dive deeper into these concepts. Through a series of phone calls and mail conversations, Shepherd learned that patterns undergird evolutionary processes. For example, studies on multi-level selection show that altruism and cooperation provide evolutionary advantages to groups, enabling them to perform more effectively than uncooperative groups.

"Groups that know how to cooperate effectively will persist by outperforming groups that can’t get along,” Shepherd said.

He also discovered the work of the late ASU Regents Professor Elinor Ostrom. Her Nobel prize-winning research studied how groups around the world successfully manage depletable shared resources, like pastures and aquifers.

"Gary recognized that her findings could serve as a model for how to design an effective reentry program," Castillo said.

Shepherd talked about how he used these prosocial principles to guide his informal leadership in prison.

He told students that he began by looking for people who behaved altruistically, then he started conversations with them about what might be possible if they worked together to create a peer education program. As the group grew larger, he made sure that everyone had a voice in those discussions and that decisions were made fairly and transparently. After getting formal approval for the program from prison administrators, he began co-creating and piloting the classes. As they were found to be effective, the program grew and was replicated at other sites.

Organizational leadership students and Castillo found his presentation inspiring and enlightening.

“I found it interesting how leadership principles were implemented into such a changeable environment," graduate student Alex Homer said. "The talk demonstrated how power balance is always in flux and that leadership doesn't always have to be a top-down process.”

“Shepherd’s story exemplifies adaptive and servant leadership," Castillo said. "He mobilized diverse people to work cooperatively for the greater good while simultaneously developing their resilience in the face of adversity.”

Shepherd was granted early release in 2021 after serving 30 years in prison, in large part due to the support of his prosecuting attorney. He’s now working on reentry projects in Phoenix and Tucson, incorporating prosocial principles there, too.

He concluded his talk by connecting evolutionary principles to ancient spiritual traditions like Daoism.

"By understanding the advantages that cooperation confers to groups, such as stability and enhanced capacity in the face of change, Gary has tremendous confidence in the future," Castillo said.

“I was really impressed with Gary Shepherd’s presentation," graduate student Kylie Kroeger said. "His perseverance for connecting and educating peers within the structured walls of prison shows his passion for evolutionary leadership. Even in the toughest environments, altruism can prevail, and with unity and cooperation there is a chance for change. There is no universal script for how to be a leader, and Gary proved that through hard work and dedication a leader can emerge from anywhere.”

This press release was produced by Arizona State University. The views expressed here are the author’s own.